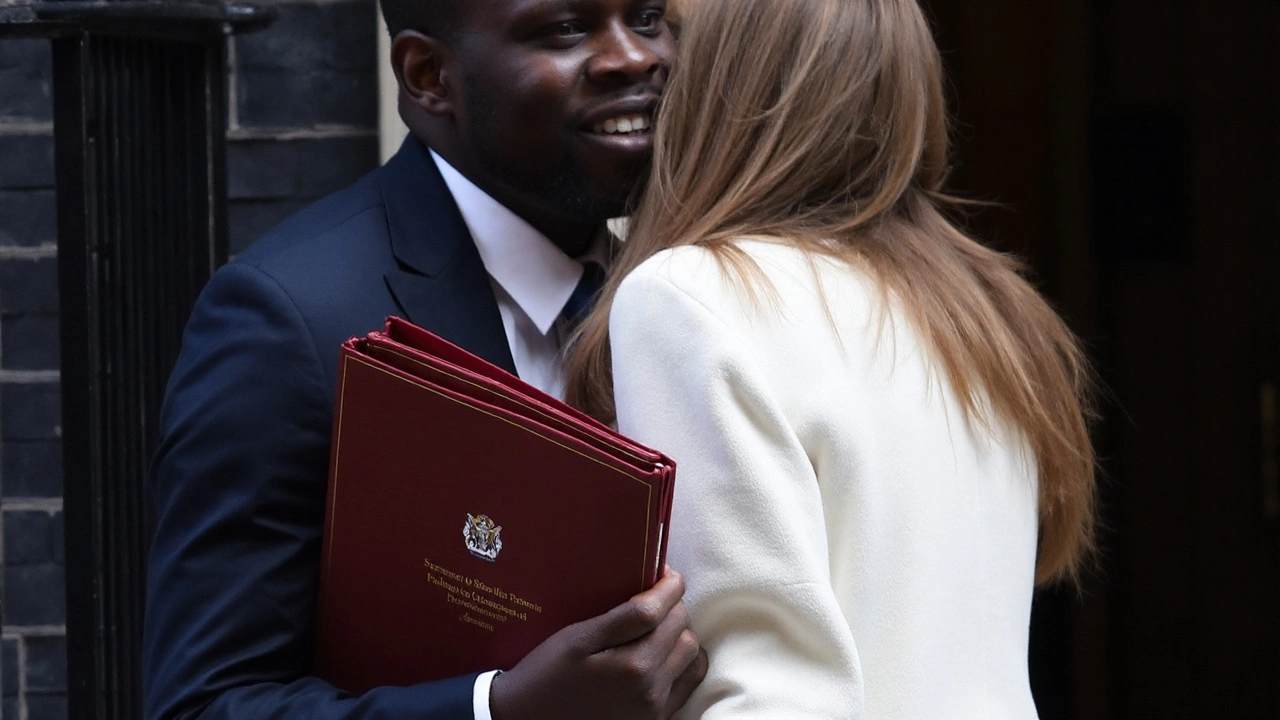

A shock reshuffle puts Lammy at the center of power

In one move, Downing Street handed the United Kingdom a new Deputy Prime Minister and Justice Secretary—and signaled a serious reset at the top of government. On September 5, 2025, David Lammy took on a rare triple brief: Deputy Prime Minister, Secretary of State for Justice, and Lord Chancellor. The appointment followed Angela Rayner’s resignation as Deputy Prime Minister and deputy leader of the Labour Party, a double departure that jolted the party’s leadership only a year into office.

Rayner’s exit leaves a gap in Labour’s internal balance and forces a broader reshuffle. Official explanations remain thin, but the political consequence is clear: Keir Starmer needs a deputy who can steady the ship while delivering on crowded domestic priorities. Lammy’s switch from the Foreign Office to the Ministry of Justice underlines that aim. It also places him among the most senior Black politicians in British government history—symbolically important and politically consequential.

Lammy comes into the job with a long CV and a lawyer’s toolkit. The 52-year-old has represented Tottenham in Parliament since 2000. He read law at SOAS, continued at Harvard, and was called to the Bar in 1994. He served across multiple departments in the previous Labour government between 2001 and 2010 and joined the Privy Council in 2008. Before this move, he was Foreign Secretary from July 2024 to September 2025, where he prioritized a reset with the European Union and worked through the grinding realities of the Ukraine war and the Gaza conflict.

That diplomatic round—his first trips included meetings in Poland, Germany, and Sweden—now gives way to a domestic brief with constitutional weight. As Lord Chancellor, Lammy swears to defend the independence of the judiciary. As Justice Secretary, he inherits a fragile system: crowded prisons, a stretched courts service, and legal aid under strain. As Deputy Prime Minister, he becomes Starmer’s chief fixer on delivery and crisis management. It’s a lot of power concentrated in one office, but not without precedent; recent governments have paired the Deputy PM role with Justice to drive cross-Whitehall reform.

This is not Lammy’s first deep dive into the justice system. In 2017, while in opposition, he led an independent review of race and criminal justice in England and Wales. That work—along with years spent scrutinizing policing, sentencing, and youth violence—will shadow his choices now. Expect him to be judged on whether policy can move from reports to results.

His transition also leaves a hole at the Foreign Office. The reshuffle will need to plug that gap fast, given the pace of events in Europe and the Middle East. But the calculation is obvious: at home, the justice system can make or break a government’s claim to competence. Court delays, prison overcrowding, and public confidence aren’t abstract—they spill into daily headlines and voter frustration.

The brief: backlogs, prisons, and the rule of law

What lands on Lammy’s desk first? The pile is high. Crown Court backlogs still run to tens of thousands of cases. Prisons are close to capacity in many parts of the estate. Probation services remain under pressure after years of reform and reversal. Legal aid deserts persist in swathes of the country. And major legislation—from parole to victims’ rights—needs follow-through, not just new slogans.

Lammy’s job blends constitutional stewardship with operational firefighting. As Lord Chancellor, he must be the system’s guardian—especially over judicial independence and the rule of law. As Justice Secretary, he must deliver: more capacity, faster trials, safer prisons, and a workforce that isn’t burning out. As Deputy Prime Minister, he will also be the government’s coordinator-in-chief, pushing other departments to play their part when justice problems cross into housing, health, education, and policing.

Here’s where the pressure will bite quickest:

- Prison capacity and safety: The estate needs space and stability. That means progress on new builds, sensible use of temporary capacity, and serious work on reducing violence, self-harm, and drug use behind bars.

- Court delays: More sitting days, more judges and staff, and fewer broken systems. Virtual hearings help, but not if IT fails or victims and witnesses get lost in the process.

- Legal aid and access to justice: Duty solicitors and legal aid firms are stretched thin. Without early advice and representation, cases drag and costs grow.

- Probation and rehabilitation: Public protection hinges on a probation service that can manage risk, not just paperwork. That requires staffing, training, and manageable caseloads.

- Sentencing and early release: Ministers face tough choices if prisons run out of room. Any change to release thresholds or recall policy will be politically charged and closely watched.

- Victims’ rights and parole reform: Delivery matters more than press releases. Victims need timely updates and real support, not just promises in new laws.

There’s also the constitutional overlay. The UK remains bound by the European Convention on Human Rights. Previous attempts to overhaul the Human Rights Act fizzled; a fresh fight would drain time and political capital. Lammy now carries responsibility for keeping domestic policy within international commitments while managing a Home Office keen on tough border and security measures. He’ll need a working relationship with the Home Secretary that is candid and coordinated.

On sentencing, expect a careful balance. Longer terms might sound decisive, but they push prisons to the brink and do little without rehabilitation. Shorter, sharper community sentences can cut reoffending when they are swift and enforced—but that takes technology that works, probation staff with time to supervise, and courts that move faster. Delivery, not rhetoric, will decide the story.

Lammy’s 2017 review on racial disparities in criminal justice will follow him into office. The core lesson wasn’t only about bias; it was about trust. If defendants, victims, and communities don’t believe the system is fair, it loses legitimacy. Practical steps—more diverse juries where possible, better data, clarity on charging decisions, and good communication with victims—build that trust. None of it is flashy, but it’s the difference between a system that grinds and one that functions.

Technology will test the ministry too. The courts need reliable, secure infrastructure, not patchwork fixes. AI can help with scheduling, transcription, and disclosure, but risks around privacy, bias, and errors are real. The Justice Secretary will be pressed to set guardrails: where AI assists, where humans decide, and how to audit the results. If he gets that wrong, appeals and delays multiply.

Money will shape everything. The Treasury will ask for proof that extra cash buys time saved and harm reduced. Expect Lammy to argue for targeted investment that pays back quickly: repairs to broken court buildings, better digital tools, and more staff in the highest-pressure teams. He’ll also need to link justice spending to savings elsewhere—fewer hospital admissions when violence falls, lower police time spent chasing court failures, and less wasted cost from cases collapsing late.

The politics are as tight as the budgets. With Rayner gone from the deputy role, the party will now work out how to fill the deputy leadership vacancy under Labour’s rules. That internal contest, whenever it comes, could stir factional energy just as the government tries to project calm. Lammy’s persona—lawyerly, direct, and media-savvy—may help. But he’ll be judged on public results more than party management.

Foreign policy won’t be far from his new desk. The war in Ukraine, ongoing tensions in the Middle East, and the UK’s European relationships all feed into justice policy—sanctions enforcement, extradition, cybercrime, and counter-terrorism need seamless coordination. Lammy’s recent contacts abroad are an asset, even if someone else now front-faces the brief at the Foreign Office.

Is this concentration of roles too much for one minister? Critics will ask, especially as the Justice Secretary’s portfolio can swamp even seasoned operators. Supporters will argue the opposite: give the person in charge of the courts and prisons the authority of the Deputy PM, and you might actually get things done. Both sides will have evidence soon enough, because the system has little slack left.

What should the public watch for in the next few weeks? First, who takes over at the Foreign Office—continuity or a new direction. Second, a clear Justice Department plan with dates and numbers: additional prison places, targets for cutting the Crown Court backlog, and measures to stabilise probation. Third, a tone shift with the judiciary—firm on delivery, respectful on independence. If those pieces land, the government buys time and credibility.

For now, Lammy owns the brief that touches the constitution, public safety, and daily fairness more than almost any other. If he can calm a restless system while a restless party looks on, he will give the Prime Minister something every government needs: proof that big promises can survive contact with reality.